Ever since our prehistoric ancestors dipped into the earth with sticks and fingers to make images on cave walls, we’ve understood the merits of natural pigments and chalks for drawing. Meet the artists who helped pave the path to the medium as we know it today.

A Timeline of the Icons and Innovators Who Blazed the Trail for Painting in Pastel

Eugene Delacroix is one of the few French artists of his time who used “skying” studies to inform his finished paintings, as John Constable had done earlier in the century. Several of Delacroix’s pastels from around 1850 appear to have been made in front of glorious sunsets out in the country, probably near his cottage at Champrosay outside Paris. He also experimented with mixed media almost a century before the practice became popular.

Jean-François Millet’s skill as a draftsman and colorist are evident here in the rich variety of greens that set off the flowers, and in the airy delicacy of the dandelions, which are shown in all phases from bud to seed.

Perhaps no other artist in history is more associated with pastel than Mary Cassatt. Her relevance to the medium lies in part with her choice of subject matter, but also in the advancements she made that prefigure numerous important modern artistic developments of the late 19th century: “The fresco-like aspect of Cassatt’s works testifies to the emerging concern with the decorative and with decorative schemes in general in the 1880s and 1890s. One wonders if Gauguin was attempting a similar effect … Large, easily distinguished shapes, a planar organization, shallow space, a generally cool palette, and an even light that abolishes most shadows combine to produce an effect of calm and repose. Indeed, Cassatt’s Mère et Enfant not only uses these devices but adds the abstraction produced by the lost profiles and scribbled lines of pastel. These pictures … form a watershed of important artistic concerns,” wrote F. E. Wissman in The New Painting: Impressionism (Geneva & San Francisco, 1986).

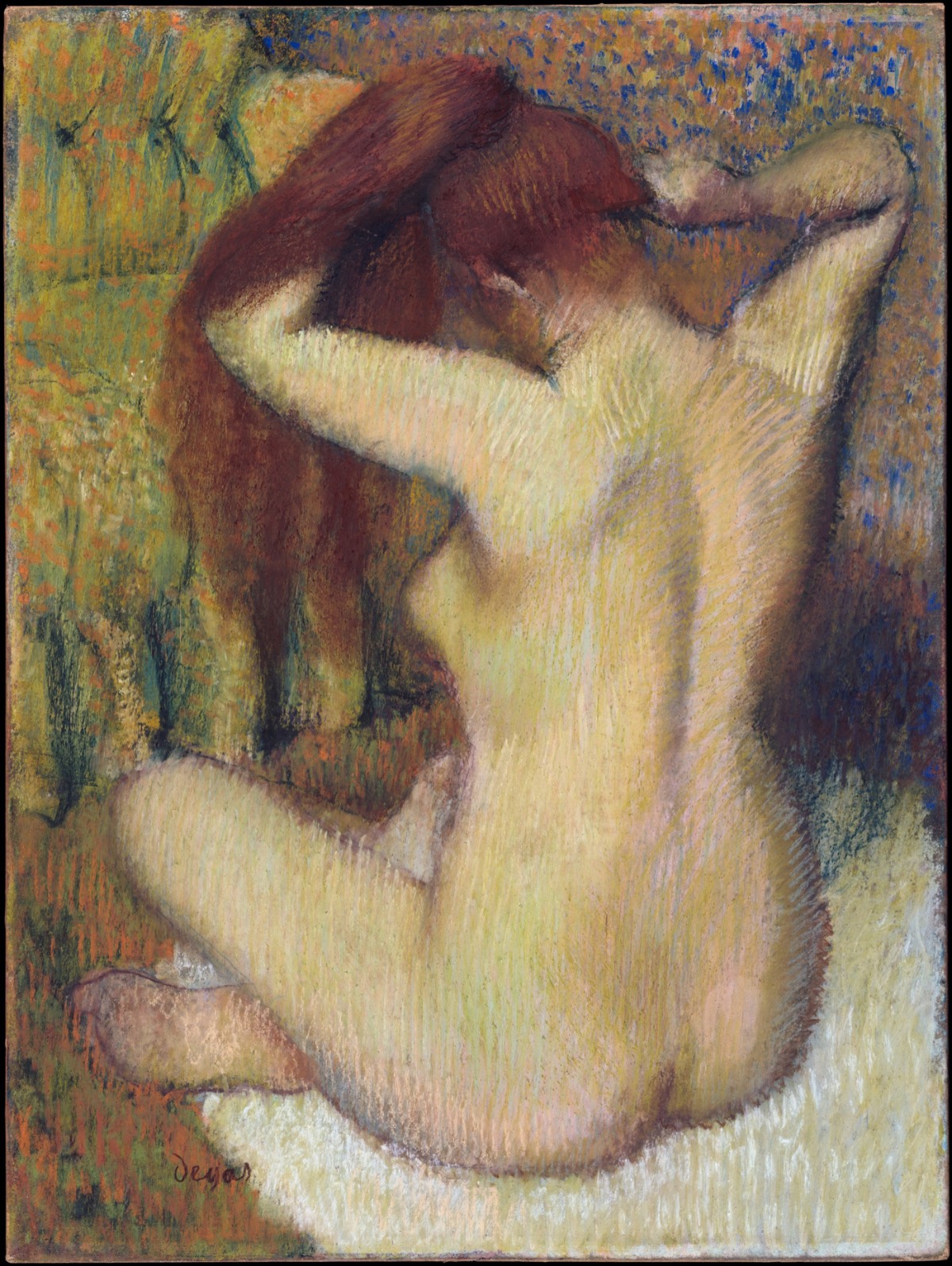

This is the second of two variants of a composition that Edgar Degas created around 1885. In this version, he used a new technique, applying pastel in so many successive layers that the pigment became burnished and the underlying paper rubbed to such an extent that the fibers were loosened and now project from the surface like many little hairs. The artist also emphasized unnatural chartreuses and greens in modeling the figure’s pink flesh, perhaps inspired by the play of complementary color contrasts in the work of such younger contemporaries as Georges Seurat (1859-1891) or Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890).

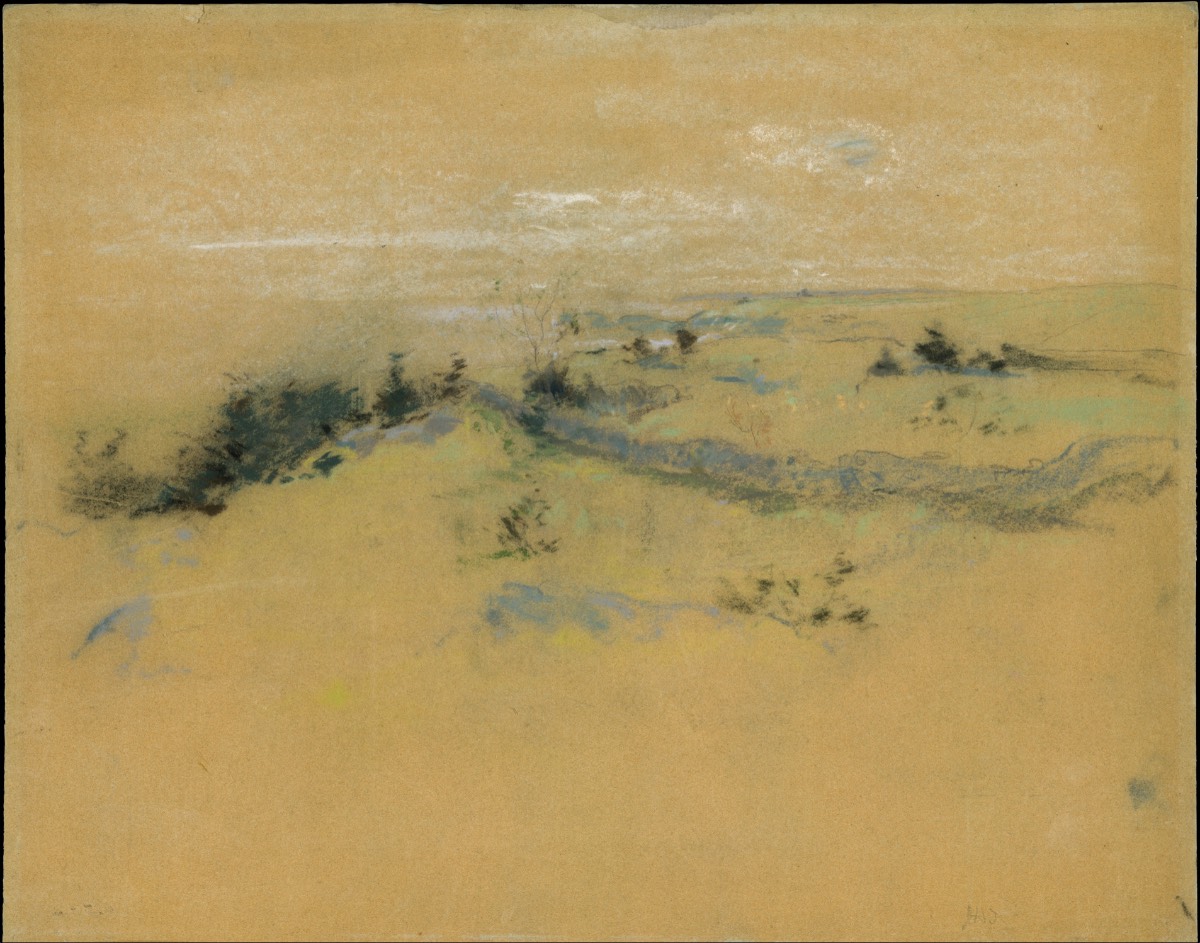

One of the most celebrated painters of his generation, William Merritt Chase also gained recognition as a master of pastel, a medium that enjoyed renewed appreciation among artists and audiences in late 19th-century America. He created this piece while running the Shinnecock Summer School of Art, the first school in the United States devoted to the practice of plein air painting. In order to capture the fleeting impressions of light and atmosphere on a sunny day, the artist applied pastel in soft, feathery strokes of pure color, some of which he smudged and blended.

John Henry Twachtman spent most of his career painting the landscape of his Connecticut property in quiet scenes inspired by Japanese prints. In these intimate paintings he often placed the horizon line at the top of the canvas, giving the viewer a sense of being nestled in the landscape.

Just as he began to receive critical and public acclaim for his haunting charcoal drawings called Noirs, Odilon Redon discovered the marvels of color through the use of pastel. Unlike La Tour, who alternated passages of color and fixative to physically stabilize the underlying layers while allowing evidence of them to remain visible, Redon animated the surfaces of his compositions by employing a great diversity of strokes. In Flower Clouds, the luminous intensity of the pastels echoes the ardent spirituality of the theme.

See Part 1 here. And for a deep dive into where the art of Realism stands today, join Stephen Bauman, Wende Caporale-Green, Dan Thompson, Glenn Villpu, and other top artists at Realism Live, November 9-11, with an Essentials Techniques Day on November 8, 2023.